Reducing Environmental and Occupational Cancer Risks Toolkit

Evidence-Informed Interventions

2. Advance a Range of Intervention Options

When we intervene and stop toxic exposures, we can prevent cancers. This truth helps to guide risk-reduction intervention frameworks used in environmental and occupational health.

The intervention framework above adapts the Total Worker Health hierarchy developed by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) to include community environments, in addition to NIOSH’s focus on work environments.

The framework is oriented top to bottom, with the top levels squarely within the wheelhouse of comprehensive cancer control programs, and the base of the pyramid requiring engagement by non-traditional partners. It is important to understand that the interventions at the base of the pyramid are likely to be the most impactful, so cancer programs and coalitions should prioritize connecting with non-traditional partners to explore whether such interventions are feasible. Different levels of interventions can be undertaken simultaneously; a combination of efforts may be particularly effective at catalyzing change.

Although useful, the least effective intervention strategies focus only on encouraging or educating about cancer risks and personal behavior changes to avoid such risks. Awareness-building alone is the least effective option because it may not lead to action.

Exposure reduction requires individuals to act on the knowledge gained, both personally and collectively. Yet in the case of environmental exposures, it is often not possible for individuals to independently undertake the protective changes needed.

For example, we can educate individuals about the cancer risks associated with radon, but personal action to test homes and install mitigation systems is necessary to effect the change needed to reduce exposure. However, installing a mitigation system may be out of financial reach for some people. Examples of community-level changes that more broadly protect the population are policy interventions that mandate the installation of mitigation systems in all new construction in states impacted by radon and require testing and mitigation in schools, government-subsidized housing, and other institutions.

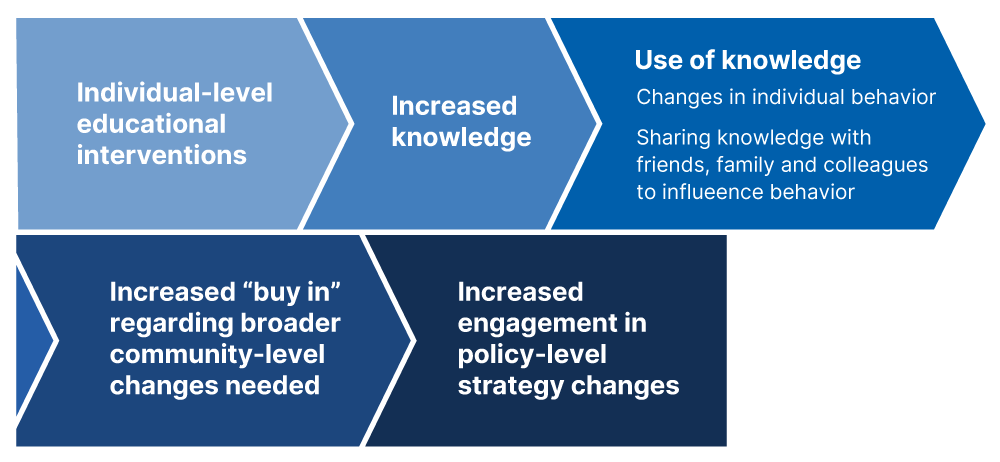

Despite being the least effective intervention strategy, encouraging and educating about cancer risks and healthier strategies is often the first step towards getting “buy-in” on the need for and subsequent adoption of more intensive and sustained intervention strategies as shown in the figure below.

Moving Beyond Encourage and Educate to More Effective Intervention Strategies

Although more involved and complex to implement, institutional- and policy-level changes that focus on Redesign, Substitution and Elimination will yield greater impact. These types of interventions will take more time and partners. However, if implemented successfully, these interventions will result in more direct reductions to environmental and occupational cancer risk factors.

Examples of intervention strategies related to Redesign, Substitute and Eliminate are shown below.

Both substitution and redesign interventions underscore the importance that sometimes it is not enough to simply focus on strategies that “stop the bad”. The public needs options of what to do or what to use instead to avoid bad consequences. Along with “stopping the bad,” there is the counterpoint need to “promote the better.” For example, concern about bisphenol-A in baby bottles bisphenol-A can act through several mechanisms to increase cancer risk (Dumitrascu et al. 2020) led to several state-level restrictions on that chemical. Without a simultaneous requirement to “promote the better,” product manufacturers were quick to replace bisphenol-A with other non-regulated chemicals (Food Packing Forum 2020) such as bisphenol-F or bisphenol-S (Siddique et al. 2021), which were similar to bisphenol A and are now understood to have similar effects (Rochester and Bolden 2015).

Newer policy models require the consideration of alternatives before restrictions are issued, such as requirements under the Safer Products for Washington Law. This law restricted bisphenol-A in thermal receipt paper because there are known safer alternatives.

Because cancer can develop many years after exposure, the primary area of interest is whether interventions effectively reduce exposure to the cancer-causing substance. This makes sense, especially when the focus is on substances that have already been demonstrated as being capable of causing or contributing to human cancers. As you’ll see in the next sections, which provide examples of interventions, metrics of effectiveness for these strategies focus on exposure reduction rather than on disease outcomes.

FROM PEOPLE TO POLICY, EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS NEED PARTNERSHIPS.

The next sections provide example strategies at the individual, institutional, and policy levels. Implementing these interventions will require collaborations with existing and new partnerships. Any strategy requires engaging partners at the earliest stages to inform viable interventions given capacities for implementation. The next sections are intended to offer examples of evidence-informed interventions that have been used in states to reduce risks associated with environmental and occupational cancers. However, your state partners will likely have a range of additional opportunities worth leveraging to support cancer risk reduction efforts.