Reducing Environmental and Occupational Cancer Risks Toolkit

Module 3: Educate & Engage

3. Unpacking Causation

State cancer plans often use statistics that enumerate what percentages of cancers are caused by specific types of risk factors (i.e., attributable risks). However, there is still a great deal of uncertainty about the question, “How much of the cancer burden is due to the environment”? We know that cancers develop through a multi-stage process, in which multiple risk factors play a role. In 2010 the President’s Cancer Panel evaluated the evidence on environmental chemicals and cancer and concluded: “The true burden of environmentally induced cancer has been grossly underestimated.”

There are at least 10 key characteristics of carcinogens that contribute to the full, multi-stage process of carcinogenesis. An agent needs to invoke at least one such characteristic to be called a carcinogen, but that doesn’t mean necessarily that that agent, acting alone, can cause the disease – rather that it is a contributing cause.

| Characteristic | Examples of relevant evidence |

|---|---|

| 1. Is electrophilic or can be metabolically activated | Parent compound or metabolite with an electrophilic structure (e.g., epoxide, quinone), formation of DNA and protein adducts |

| 2. Is genotoxic | DNA damage (DNA strand breaks, DNA-protein cross-links, unscheduled DNA synthesis). intercalation, gene mutations, cytogenetic changes (e.g., chromosome aberrations, micronuclei) |

| 3. Alters DNA repair or causes genomic instability | Alterations of DNA replication or repair (e.g., topoisomerase II, base-excision or double-strand break repair) |

| 4. Induces epigenetic alterations | DNA methylation, histone modification, microRNA expression |

| 5. Induces oxidative stress | Oxygen radicals, oxidative stress, oxidative damage to macromolecules (e.g., DNA, lipids) |

| 6. Induces chronic inflammation | Elevated white blood cells, myeloperoxidase activity, altered cytokine and/or chemokine production |

| 7. Is immunosuppressive | Decreased immunosurveillance, immune system dysfunction |

| 8. Modulates receptor-mediated effects | Receptor in/activation (e.g., ER, PPAR, AhR) or modulation of endogenous ligands (including hormones) |

| 9. Causes immortalization | Inhibition of senescence, cell transformation |

| 10. Alters cell proliferation, cell death or nutrient supply | Increased proliferation, decreased apoptosis, changes in growth factors, energetics and signaling pathways related to cellular replication or cell cycle control, angiogenesis |

Abbreviations: AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; ER, estrogen receptor; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor. Any of the 10 characteristics in this table could interact with any other (e.g., oxidative stress, DNA damage, and chronic inflammation), which when combined provides stronger evidence for a cancer mechanism than would oxidative stress alone.

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4892922/pdf/ehp.1509912.pdf

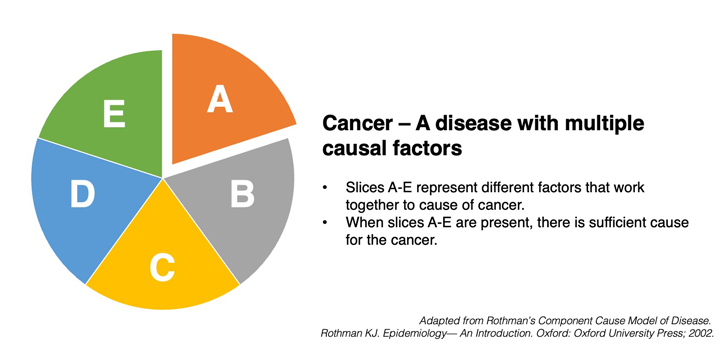

It is important to understand that cancers arise from a multiple factorial process. To see why this is important, consider the metaphor of a “pie”, which represents the range of factors that need to occur for cancer to develop. This pie is a simplified metaphor to represent the complex causal web of factors that contribute to cancer over a person’s life span. Typically, a single risk factor such as tobacco use cannot contribute to every factor necessary to cause cancer. This is why all of us know people who smoked, but never developed cancer. However, use of tobacco will contribute to several factors/ slices that begin to complete the pie.

The pie metaphor is useful for cancer causation because it demonstrates that just as there are multiple factors that contribute to cancer, there are multiple ways to prevent it. For example, smoking and diet are important risk factors for a number of cancers. Although changes to policy and individuals’ behaviors can reduce risks, successful cancer prevention efforts will require also addressing other co-occurring risk factors, including exposures in our environment and workplaces. Thus, we should do the best we can to minimize exposure to all carcinogens wherever possible.

Recently, scientific researchers have demonstrated that environmental chemicals, including those that disrupt the endocrine system, are more important in cancer development than previously thought. The Halifax Project – featured in an issue of the journal Carcinogenesis – concluded that many endocrine disrupting chemicals, previously not identified as carcinogens, may, in fact, play a role in tumor development. Thus, although these chemicals will give negative results when tested in standard rodent cancer assays, they may nonetheless contribute to the development of cancers by contributing one piece to the pie of multiple causal factors.

To learn more about this topic, listen to an interview below with Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee, Pulitzer Prize-winning author and assistant professor of medicine at Columbia University regarding how our traditional models of detecting carcinogens are falling short.

Insights on the evidence described by Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee underscores the following: